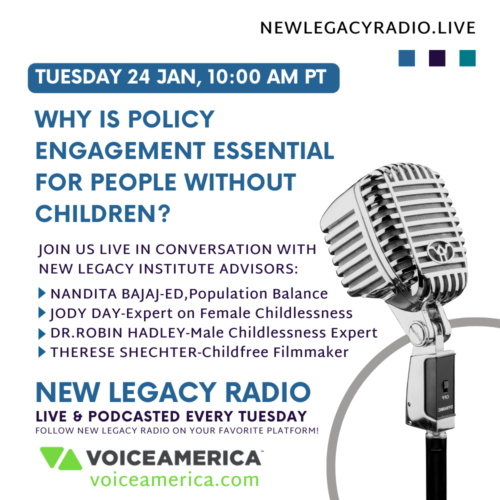

Why is Policy Engagement Essential for People Without Children? on New Legacy Radio, a Voice America Show. [Episode recorded 23 January 2023]. Featuring Christine J. Erickson, founder of New Legacy Insititute in conversation with New Legacy Institute Advisors: Jody Day (founder of Gateway Women and author of ‘Living the Life Unexpected’), Dr Robin Hadley (adademic researcher and the author of ‘How Is a Man Supposed to be a Man? Male Childlessness – a Life Course Disrupted’), Therese Shechter (founder of female-led production house Trixie Films and director of ‘My So Called Selfish Life’) and Nandita Bajaj (Lecturer on pronatalism at Antioch University and Executive Director of Population Balance.)

Click here to listen to the full episode or search ‘New Legacy Radio’ wherever you get your podcasts. You can follow NLI on Twitter @NLInstitute, Instagram @newlegacyinstitute and LinkedIn @new-legacy-institute and find out more about how you can volunteer, join or support financially on its website at New Legacy Institute. Abstract and full transcript below.

ABSTRACT

In today’s episode we will discuss the value of policy engagement for people without children, and why it matters for our community. We will look at the historical and current influences pronatalism has on social policy, workplace leave policies and benefits, and public policy.

We will also assess the ways in which pronatalist culture and policies impact the daily lives of people without children, and why we must organize for collective action now.

Joining us for this conversation will be New Legacy Advisors, Nandita Bajaj, Executive Director of Population Balance, Jody Day, who is an expert in female childlessness, and founder of Gateway Women; Dr. Robin Hadley, who is an expert and researcher on male childlessness, and Therese Shechter, who is a childfree filmmaker, and founder of Trixie Films!

Tune in to learn more about New Legacy Institute’s purpose in advocating for policy change, and creating a social justice platform for people without children. We will also share how our community and allies can become part of the change we envision for our community and beyond!

FULL TRANSCRIPT BELOW If you wish to view/download/print the transcript go to New Legacy Institute website here. The transcript below is used with permission. Copyright 2023. New Legacy Institute. All Rights Reserved.

I am very fortunate to have with me, four of the Institute advisors and experts on our growing global community of people without children, and on pronatalism, specifically. We have in the room, Dr. Robin Hadley, an expert on male childlessness, and a wonderful researcher who has made significant contributions to this field; Jody Day, who is the founder of Gateway Women, and an expert on female childlessness; Therese Shechter, who is a childfree, filmmaker, and you may recognize her from her fabulous film ‘My So-Called Selfish Life’, and Nandita Bajaj, who is an expert on pronatalism, and teaches courses on pronatalism, as well as being the Executive Director of Population Balance.

Welcome, everyone, and thank you for being on the show today. It is great to have you here. So, I’ve been wanting to have this conversation for a long time, and really appreciate you being part of this conversation, with all of your perspectives that you bring to the table. I think, you know, as a community, we have done so much in the past decade or more to come together in recognizing who we are, creating support, and greater recognition of who our community is, and what we need. And now we’re looking at sort of a next level, and what do we need to do next, to really create impactful change across the board really.

And I just ask why does policy matter to us, as people without children? And why are we even looking at this as an Institute? I think that’s what a lot of people want to know. It’s a kind of a departure from where we’ve been, and where we’re going. And so today, I’m hoping we can kind of close that gap for others and invite them into this conversation to take some collective action. So maybe we can just go around, and I’d just love to hear from each of you generally, the perspectives that you’re coming from and why you were drawn to coming together within the Institute.

Jody Day: I’ll kick off, it’s Jody. I guess I’ve been sort of active in the childless side of this conversation for coming up on 12 years now, since I started my blog. The blog was called ‘Gateway Women’ and it became a global organization called Gateway Women. And it’s in many ways, well, these days I’ve been called the elder stateswoman of childlessness, which I’m going to take as a compliment. And I think what I’ve really noticed over the years, is that the same issues come up in women’s lives.

Now, in a way, Gateway Women is sort of speaking to a different generation. To me, it’s starting to see a lot of the women who are grappling with coming to terms with involuntary childlessness are in their early 40s. And I’m now in my late 50s. But the same issues are coming up again. Now, some of those issues are personal and social issues, which really, really speak to how pronatalism filters through every section of our society, but a lot are to do with the workplace and with inequalities to do with pensions and taxes and systemic unfairness that is baked into the way our societies are structured.

Now those are things that policy can tackle, that there’s in a way by tackling, also, by taking it seriously, and taking them to organizations as policy issues, we can begin to move the dial away from this being a sort of a group bleating about its needs. Because there’s often this idea, “Well, we don’t really care about childless or childfree people, we’ve got more important stuff to be dealing with.” And there is a real lack of recognition that this is a very, very large and growing demographic. And not only is it unfair to keep treating us like we don’t have needs and that we don’t make any contributions. It’s also kind of undemocratic, unhelpful, unproductive, and ultimately, is not helping society. And that includes everyone else’s children, you know, we are actually part of society. And if our needs were actually included, and that’s what policy would do, we could actually make more of a contribution, not less.

Christine Erickson: Thank you for that Jody. Therese.

Therese Shechter: Yeah, just to build on what Jody was saying, speaking from the childfree perspective, and having worked on this film for many years now, I’ve come into contact with 1000s of people who have a lot of issues with how they’re allowed to live their lives and the complicating factors of their lives, simply because we are not at the table. And we are not taking part in these conversations, we’re not considered important, we’re actually considered somewhat of a menace, to be honest, because we are not giving over our reproductive organs for the betterment of the economy.

So, it is a challenging thing, but as Jody said, the populations are growing and like one of my favorite studies actually is Pew Research Center, from just a couple of years ago showed that 44% of nonparents aged 18 to 49 say it is not likely or not likely at all, that they will ever have children. That is 44% of nonparents of what we call childbearing age. This is up 7% from four or five years ago. So, this is a rapidly growing demographic, and stepping aside from like, why you know, or what’s good or bad about it; it’s a growing demographic for here, we’re here and we are not being considered an important enough part of society to actually think about what we might need. Although, we are important enough to exploit, and we can talk about that later.

Christine Erickson: Excellent. Thank you for that Therese. Nandita.

Nandita Bajaj: Thank you. I’ll jump off of Teresa’s point here about the impacts of these policies that are hugely pronatalist not just policies, but also a lot of the cultural norms that disenfranchise, stigmatize and ostracize people without children, in all sectors of society, whether it’s educational institutions, the health care system, government, law enforcement, you name it.

And the reason I think that shift in policy is so important, is well, there are two ways of shifting culture and one is raising awareness, you know, which we’re all doing in our own ways. And then the other one is shift in policy. And they both feed into one another. And the reason policy shift is so important is because it has a much greater influence in shifting cultural norms than simply awareness-raising campaigns. And I’m so thrilled that you are leading the charge, Christine, and that we’re all doing this work together.

Because not only are these policies that are super pronatalist, and anti, folks who do not fit the dominant narrative, they actually are also causing a lot of ecological and societal crises, and working kind of within the field of looking at the interconnection between pronatalism and population growth and human supremacy, and how we look at all of nature, it’s really important to challenge these specific policies both at individual rights base levels for how we’re treated as individuals, but also what these policies have the power to do in terms of striking a better balance with nature and other beings in nature.

Christine Erickson: Absolutely, thank you for that, Nandita. And you know, I really appreciate the scope-and I know we’re coming right up to Rob-of this particular group, because of the breadth of perspectives that you bring. You know, there are all these layers that interplay, from the environment, to our personal lives to corporations to, you know, where not only where it’s impacted, but where it is impacting our very environment, let alone population growth. So over to you, Rob.

Dr. Robin Hadley: Hi. Well, all the above, I think, is what you described, and I just know it down policy environment. And that interchange, that we all live in an environment that is policy driven, whether you realize it or not consciously or unconsciously, with the societal frameworks that are embedded through policy, and embedded in ourselves, of what’s good and bad, and how to behave. That’s, I think, how important policy is, is the unseen impact and the structuring and structure of policy, personally, politically, and that policy and politics really go together. We are all political, even, not being political, is being political.

And so, from my perspective, policy is so important, as you’re getting older, which institutes and organizations you may come into contact with, for the childless, for childless men, from my perspective, is how invisible we are, because we’re not counted. And so, demographics, you know, who decides who’s counted, and who isn’t? That’s a policy decision that reflects so much on the background to the people who decide who’s counted and why they’re counted, and why they’re not counted. And what that reflects, that’s a whole can of worms around that.

So, policy is so important, and as Nandita said, great having grassroots organizations raising stuff, but that needs to grow into the environment, into the political environment, and to be recognized and to hold a mirror up to that environment, and to ask why, and how, and because. So, yes, so policy is really, really important.

Christine Erickson:Thank you so much for that, Rob. Yes, I think, as you spoke to the demographics, and I think about the important research that you and a few others have been doing, looking at our demographic, the need for that clarity of data. I think, you know, I had wanted to speak a little bit to, you the history, if you will, of pronatalism, which is another can of worms, a from the beginning of time kind of conversation, right?

But maybe we can look at both of these things together. In looking at historical and status quo influences, economic models, capitalism, and all of that in hand with what we’re seeing now, in so many of these, you know, articles about, economic crises based on population “crises”, and what that really means, and why we keep seeing that emerging, particularly for several countries. I think China was the most recent one to be written about. And I know Nandita has written and spoken a lot to this. So, I’d love to look at that, and what is true and what is not true and what happens when you have a missing demographic. Nandita.

Nandita Bajaj: Since you just brought up the crises that are front and center and all of our news channels about the quote, unquote, “aging crisis”, the “depopulation crisis”, the “baby bust crisis”, name it whatever way you want that reduces individuals into reproductive vessels. It reduces people into economic inputs and outputs. Whatever is being shared really in the news is not about people. It’s not about individual rights. It’s not about our well-being. It’s about this really ridiculous nonsensical pyramid scheme that we’ve created that relies on perpetual economic growth, to continue to grow the GDP, which we have enough metrics, we have enough data to suggest that GDP growth is not a great proxy for human wellbeing or planetary health.

And yet, we keep serving to that one ridiculous goal. Also, inherent in so many of these alarmist narratives is a very ageist narrative that people once they hit a certain age, and it’s a very outdated age that we’re still relying on, which is 15 to 64, of what we call the working population, is basically saying anybody who reaches that age is then a burden to society, and is no longer contributing to society. And there are so many issues, of course, ageist issues that are propped up within institutions that don’t allow people to continue to work and be productive and be fulfilled by remaining active and work. But also, it reduces them into these, you know, kind of, quote, unquote, “elderly, frail burdens” to society. And then the idea is in order to prop up the healthcare to support them, the only way, the only creative way we can think of is to have people make more babies, so that they can grow up and contribute to the economy to then pay for the elderly.

It’s the most ridiculous Ponzi scheme out there, and I just really wish people would call it out for what it is; a Ponzi scheme, that is really lacking creativity, and it’s lacking centering of planetary and individual well-being. And you know, I’ll speak to that a bit more later. But I want to pass the mic over to other folks.

Christine Erickson: Thank you, Nandita. A Ponzi scheme, indeed.

Jody Day: I think, just speaking to Nandita I too see the shocking ageism and ageist narratives that are coming forward, and what it doesn’t in pure economic terms, these arguments also don’t include how much people in the last third of their life, let’s say from 60 to 90, actually are massive contributors to the economy in other ways, not necessarily through working, through caring through contributing through buying things. They’re actually a huge net asset.

The medical expenses and the caring expenses, when they’re put against how much you know, the economic assets and contributions of this group, it’s not as shocking as people think. But that once again, that’s not the argument that totally interests me, like you, it’s like, there are so many creative solutions; creative intergenerational solutions that can include all of us in supporting our elders, and also allowing our elders to be part of our society. They are really not being spoken about or centered, or considered as part of this argument. I agree. It’s, reducing people into economic units, and also scaring people with the language like a grey tsunami, when in actual fact, a world that is becoming a world with more elders in it, is a massive success story. It is not a disaster. They are an amazing asset to the world, and to future generations, if we can turn this story around.

And that’s why policy is so important. Because I agree. I mean, we have recently, Christine interviewed a friend of mine called Trish Faulks, who runs Just Me and Lilley. You know, she’s in her mid 70s, and she would love to be working more because she would like the intergenerational connections and community that come with being in work. And she’s struggling because companies say they would like to have older people, but there are still sort of limits in the type of jobs and limits even in the application processes that make it difficult, and those are policy decisions.

And just yesterday there was there something in the UK where they are planning to have a middle-aged, I quote, middle-aged love Island is being planned. Everyone has to be a parent. In order to qualify to apply for the show, you have to be a parent. Now I’m sorry if that was any other group. If that was people of different sexualities, ethnicities, abilities, it will be called out for the shocking prejudice that it is. But somehow, only parents are allowed to go to the middle-aged love Island. Frankly, they’re welcome to it. That’s not my point.

Christine Erickson: That is what I was thinking, as well. Thank you, Jody. Therese.

Therese Shechter: Sorry, I’m just I’m still I’m still thinking about middle-aged love Island, which, if somebody invited me, I would change my name and move to another country. Okay, anyway, pronatalism. Yeah, I think just digging into pronatalism a little more, aside from capitalism, which is sort of what we’ve been talking about, pronatalism plays really well with patriarchy. Pronatalism, the pressure for people to reproduce in the most basic definition I suppose, reinforces a nuclear family structure, reinforces women staying home to raise the kids. All of these things that we know are not necessarily what a society even looks like, at this point. But it is it is reinforcing these ideas of gender roles of women to this, and men do that.

We’re thrown back into the Victorian private sphere of womanhood, and public sphere of men doing the important work, that kind of thing. So that’s also, I think, wrapped up in all of this, and it is nostalgia in the US, for the good old days. You know, the baby boom. The baby boom is basically a very fast up and down trend. It was a complete anomaly in our fertility history of the last 100 years. So now we’re going back to this kind of, “Oh, back when women were pushed out of the workforce and had to stay home in the suburbs to raise their kids, wasn’t that great? We should do that again, because that would be great.”

The other thing that pronatalism works really well with this nationalism. And again, speaking, as somebody who’s lived in the US for 30 years, there is so much white supremacy baked into American pronatalism and fertility rate panic, and has been for at least 150 years, this fear of, quote unquote, “white race suicide.” That the white race, again I have this in quotes, is being diminished by the over reproduction of people of color. Immigrants. Just it’s a constant discourse right now about this. Replacement Theory, I mean, just a lot of really heinous ideas about how society should function. And fertility rate panic has a very often been translated into white race, suicide panic, at its most essential form. So pronatalism is very insidious. It is not, in my opinion, a very positive force in any definition. And everything that we’re talking about, in terms of better policies, kind of grows out of the damage that pronatalism has done to our society.

Christine Erickson: Yeah, very well said. Yes, it grows out of the damage it has done to our society. Absolutely. And when you were speaking, and thank you for, for bringing all of that up, as well. When I was thinking of, you know, I’ve got these images in my head of economic units. And we’re just going on this way, you know, children are an economic unit, the family, the nuclear family is an economic unit. I mean, that’s how it’s reinforced, you know, and I look at the demographics, I think about all the conversations I’ve had in the past year, or nearly a year, here and within the Institute, and think about the diversity of the ways people are living the ways families are structured, the way friends are living together, all of the different ways that we can manage personal economics.

And the options I mean, are limitless, let alone to speak of people who are single and without children, you know, they also have not been considered in a very different way. And the breadth of what is missing in policy, let alone socially or social services and things attached to that, which you touched on Rob, is just exponential in addressing this. I just, I don’t know, it’s overwhelming, sometimes and if you break it down break it down to, as you said, Nandita, “a ridiculous Ponzi scheme.” You know, we know where those end up, we know what they are; you know, it is time. It’s time to shut it down.

With that, we’re going to take a short pause, and we will be back for this fabulous conversation with Robin Hadley, Jody Day, Therese Shechter and Nandita Bajaj. And we will discuss more about policy and the impact on our community, and how it universally can be a positive shift for all of us. We’ll be right back.

Welcome back, everyone. And thank you for tuning in. You’re listening to New Legacy Radio, and today we are discussing policy and its importance for the community of people without children. Here today with us are Dr. Robin Hadley, Jody Day, Therese Shechter, and Nandita Bajaj, and we are going to continue the conversation that we started in the first half, looking at the impact and the damage that Pronatalism has done from a policy and social perspective, and what is, as Nandita aptly deemed, a “ridiculous Ponzi scheme” in terms of how we are creating false crises, and looking at economic models that do not work. If they ever did, they are no longer working for the demographics and the reality that we are living today.

So welcome back. And thank you again, everyone for being here. One question I was thinking of, and we can take this in a different direction if this doesn’t sync right now. But I guess the question of “why now?” You know, are we, being very definitive in coming to the table and finding ways to influence policy. I mean, I think it’s obvious in all of the things that we’ve said, but I think many people will ask, you know, why now, why is this important, now? Where has this conversation been? And, you know, is it just another diversity conversation? Is it another checkbox? Really, why, why now? What’s the urgency and is there an urgency?

Jody Day: I think I can speak to that a little bit from the numbers. I mean, about sort of five, six years ago, I was starting to see so many more women joining what was the Gateway Women online community, who were childless by circumstance then. So, I was born in 1964. And in the UK, one in four of us, of my cohort did not have children. And that was mostly 90%, not by choice; those numbers are changing as well.

But we’re seeing more and more women who are not having children who would have liked to have had children because they’re not finding a willing or suitable partner during their fertile years. Now, I’ve been looking at correlating some of the UN data on the massive, massive rise in single women around the world. And the UN defines that as women who are neither married nor in a union is how they describe it. So, it captures both those living together, and those not married, and it’s gone up sort of about 70%, you know, and it’s growing. And it’s going in all countries. I mean, I did this research when I was doing a TEDx talk about single non-mothers in India and how it’s risen there.

But when we start to look at the numbers of women around the world, who are single, we correlate that with in the UK with data that came out last year from the Office of National Statistics about the number of women who had not yet had a child, aged 30, this was the highest it had ever been, it was almost 50%. Now the age of the mother at first birth, is a very clear indication of how many more children she may possibly go on to have. And the later that first birth is, the more chance there is that she will not have children.

So, this big, big growth that I’ve been seeing, anecdotally the evidence is starting to come out. And I think that the UK and perhaps the US are very, very easily on track to be one in three women reaching midlife without having had children, as it already is in Germany (although more recent cohorts are showing a lower percentage) and in Japan it is almost now one in two, because that statistic, once it’s been going on for long enough, you have an exponential decline. So, I think it’s the one of the reasons we really need to get around the table, as Robin says, is there are going to be so many of us, and including our needs, and our contributions will be a really, really important part of shaping the world over the next 50 years.

Christine Erickson: Absolutely. Thank you, Jody. Nandita.

Nandita Bajaj: Yeah, and to answer also your question about why now, of course, I think people without children, just like people across all types of you know, whether we’re speaking about ability, gender, ethnicity, etc. I mean, it is part of the DEI equation. We have been underrepresented across the different sectors, across policy level. And it’s about time, especially as we do see, as Jody said, a rise in numbers of people who represent non-dominant lifestyles, non-dominant traditional families, as Therese called it. So definitely, that is a reason.

The second reason I think is also the, the alarmism around declining populations is at an all-time high. And that perfectly correlates with declining fertility in industrialized countries. And it also perfectly correlates with the level of empowerment that people have, especially women to choose what they do with their reproductive capacity and with their lives. So, you know, we are also seeing an increase in the number of people choosing not to have children by choice. And that is seen as a threat to our governments, to our nations that rely on an ever-growing population.

And to go back to something Therese said, there’s also been a rise, and as a result of a rise in liberalism, feminism, reproductive autonomy across industrialized countries, there’s also been, you know, a backlash and a rise in right wing populism that wants to send people back into their gendered roles, so that we can continue to perpetuate our own type of people. And so, because of this, baby bust alarmism, which is kind of at a fever pitch right now, there is an even greater need for or for people like us to push for different policies that are challenging not only the efficacy of these narratives, because they are paper thin if they exist at all, but also because they are grossly unjust in terms of just completely marginalizing people who are making liberated choices, and undermining reproductive autonomy.

You know, and in terms of why the efficacy is so low on these economic-based narratives is we have enough studies to actually show that in countries that have aged the most, there are so many benefits. Instead of you know, governments are talking about there aren’t enough workers or you know, we’re running out of people in terms of employment, we’re actually seeing less unemployment and less underemployment. There’s also this, you know, the rise in proportion of older citizens, there is this idea that they become a burden on society, but because of longevity, we’re actually increasing also the quality of life. And people aren’t experiencing those health care costs that the government keeps, you know, alarming us about until much later in life, maybe in late 80s, and 90s.

And so, I think if even if we are talking within the current economic scheme, and we need to speak the language that policymakers will hear, we need to challenge that even within the current economic model, these are ill-founded and false narratives. And, you know, while I’m in favor of completely uprooting the current economic model, in favor of something like a well-being economy or a de-growth economy, we still need to say that they don’t hold water, these narratives even in the current model,

Christine Erickson: Thank you so much for that, Nandita.

Dr. Robin Hadley: Brilliant, Nandita. Absolutely, what a fantastic summary of a really complex subject. And I think I’m going to summarize your really lovely, detailed summary, it is that there’s no simple solutions to complex problems. And what is offered is generally a simple solution. It’s a black-and-white solution to a multicolored, multidimensional issue.

And I think when it comes to older people, it’s the marketization of that, issues are about frailty and all that sort of thing. For the government, they’re saying, “Well, how who’s going to pay for that?”, but for industries involved with that, what they’re seeing is the dollar sign with those people, that those aren’t people, they’re pitch points to be extracted for the world to be extracted from and to be dominated by.

I think one of the other simple themes I come across is anti-migration. Whereas migration over many generations, has actually saved many countries and many Western countries have grown because of that. It’s absolutely based on people coming in and doing those low-skilled and skilled jobs and building up to generate the economy and their success. So, I think, yeah, it’s who benefits from this narrative is one of the questions and to get in that narrative and adjust it at the correct level and to challenge it, as well, because there’s a very close link between industries of various sorts and politicians. In some countries, it’s very, very clear that link, and in others, it’s hidden, but it’s definitely there.

Christine Erickson: Thank you, Rob. Jody.

Jody Day: I just want to say, Rob, to your point about immigration, I think as more and more countries, when women get better education, economies develop for want of a better word, reproductive rights and access to birth control becomes a possibility, then the idea that there’s always going to be people who are going to want to migrate. That is also something in a way, that’s also still seeing people in a way as kind of economic units that can be moved around on a board. And I think that is something that perhaps also will settle into a new pattern, as we move into a de-growth economy, which I think is where we’ll end up whether we go willingly or not, is probably where we’re going to go at some point. Nandita, I’m very much with you.

But to Christine’s point about why now, something, which is unpleasant to think about, but I think we are seeing it in some of the more sort of reactionary comments, and some of the right-wing anti reproduction right things that have been happening in the US and other places, is, I think that the fear-mongering around population decline, and allying that to people not having children, could lead to some really, really horrible hate crimes against people without children, for whatever reason. We could see them being denied access to, you know, to legal things, to health care, to housing to all kinds of things because, as Rob said, you know, people do tend to often look to and the media encourages this, simple solutions to complex problems.

And I have a fear that in 20 years-time, when the rubber is really going to meet the road on this, that it could be a sense of it’s all their fault. You know, it’s all the people without children’s fault. And I think it’s really important that as a group, which is why you know, I’m such a, you know, a big fan of what Christine is doing with New Legacy Institute. I think we need to find our political voice. And as Rob said, policy is political, because I think it could get quite nasty. And I think we need to be prepared for that. And we need to get the law on our side. We need protection as a group, really, really strongly. We need to be recognized as a group that has rights and has a voice that is equitable with everyone else. I don’t want to take rights away from parents and families, I want to support them, but not at the cost of my rights

Christine Erickson: Thank you, Jody.

Therese Shechter: Thank you, just very quickly, because I know we’re going to move on, what Jody is describing is real and happening. It’s happening in Russia. It’s happening in Hungary. It’s happening in Turkey. It’s happening in nations that have become extremely right-wing. When rewarding people for having children, doesn’t make them have more children, the next thing you do is punish them. And this is a trend that is very real. It’s illegal to be a childfree advocate in Russia. It’s illegal. What we’re doing, if we were in Russia, would be illegal. So just wanted to drop that in there.

Christine Erickson: Thank you for that Therese. Yes. And I mean, the idea of rewarding we’ve read about that in many countries, I think Brazil as well. Yeah. I mean, I think so many systemic things for so long-and I won’t go off on a tangent about leadership and consent, which is something that I focus on in my other work-but I think for so long, there’s been this, you know, we spoke about patriarchal control, and systemic injustice is that they’re not working anymore. And, so rather than shifting that, or meeting, that there’s really not that capacity, because somewhere, it means someone is losing control. It means losing power. And these are desperate measures. I mean, to incentivize people with a financial reward-I don’t care if it’s $5 or 5 million- to have a child, that is desperate, that is desperate, and it is not healthy. It is not well, it is not in the interest of individuals, or families, or communities, or countries or the world, at any level.

And the desperation that is there, you know what will break that, or what will break before we are in these conversations? I don’t know, or are we at the bottom? You know, that’s what it feels like a lot of the time. Is it that broken, and how will those who are driving that let go toward something that is far more actually universal and beneficial? I think from our perspective, that not only represents and supports our community, but when we look at policy and we have our policy conversations, we talk about universal policies that are healthy for everyone; reproductive autonomy, population balance, you know, which is a brilliant name, and my favorite phrase.

All of these things that are impacting our, environment, our resources, the way that we eat, or the impact on our health. When do we stop, and how do we stop it? You know, we’re so far gone. But it’s not over. And I think that is part of why now, and all of the beautiful things and brilliant things that you’ve shared, because it’s on every layer of this planet is in every culture, it’s our food sources.

New Legacy Institute isn’t just an organization to say, you know, look at us, we’re here too; well, it partly is because that’s also true, right? We’re not seen. But it’s because we’re coming to this at a point where we are looking at things systemically, and we are a large part of that populace. But I think what we are doing differently is approaching it from a systemic perspective, just as Population Balance is, for example. And I think that’s a key difference in how we’re coming to the table, or wanting to influence these conversations. Who raised their hand first? Therese.

Therese Shechter: I think that one really positive thing, and the reason that I am working with all of you and thrilled that New Legacy Institute exists, is that there are ways for us to get into the middle of these things. So often, it’s the individual who needs to fix their problem, which is usually within a large corporation. They’re practically powerless to address inequities that they’re finding in the workplace, for example. So, it’s really the institutions that need to get educated and not just educated because some of them have policies, but they don’t really follow them because management is not getting involved in these things. So not just policies, but roadmaps. What is the roadmap to creating a more equitable workplace? What is the roadmap to getting medical professionals to understand that people have certain reproductive needs that need to be addressed very seriously. So, I think this is part of our mission is to help people who the workforce is growing of people who are having these issues, basically. So, we’re helping to address it.

Jody Day: I think one of the things that’s really needed is more data, kind of speaking to Therese’s point, because whenever I speak to organizations, or individuals or magazines, or podcasts, you know, I drop into numbers, and people are consistently surprised how many of us there are. But also, when you start to drill down within organizations like Therese was saying, you know, those that do lead on DEIB, those that actually walk the talk and things like that this stuff affects the bottom line.

If people want to do the economics, an organization that is actually more equitable, that is going to retain its key talent, its nonparent talent. I mean, I have heard so many stories over the years, and my story has come from, you know, from women, of women who have left organizations because of the way they are treated as a nonparent. And these are women who’ve worked in organizations for 10-20 years, have covered maternity leave for many other people are kind of skilled across so many areas of the business, these are key women in the business, and they lose them because they don’t listen to what these women are asking for. They’re not asking for the world. They’re just asking to be recognized for the contribution they make and how much they do in soft and hard ways, unpaid to support parents in the business, and how they’re not prepared to do that anymore.

So, they actually, businesses really benefit from embracing and understanding the issues of people without children in the workplace. And when workplaces are forced because of policy, which becomes law, to pay attention to these kinds of issues, as they have done with the LGBTQ community over the last-in my lifetime, it has been transformed. When it becomes policy within a business, because it’s law that it’s got to be part of your policy. That means that people who are not part of that lifestyle, to use a word I hate are sort of forced to think about it, are forced to consider it. It’s not their experience, but they now have to think about it for their workforce and coming into contact with those thoughts and those people and those issues means that they take those thoughts and understandings out of the workplace into wider society.

You know, in the 70s, when I was watching TV programs, a gay character was just there to be a figure of fun. They didn’t even have to be funny, just the fact that they were gay meant they were funny, that’s now a hate crime. That’s what policy change does. It doesn’t just change how things are done. It changes the way we are perceived in society. People without children contribute so much, and policy change will help people to start to see that we contribute. We are not a deficit, we are actually, you know, an asset to society. So, there’s a big story to be changed, and policies are a really important part of that.

Dr. Robin Hadley: Just really quickly, one of the things that are missing from a lot of data is the men, because men really aren’t counted on lots of sort of levels. And there’s lots of reasons for that, but one of those things is maybe nations don’t want to see their men as being weak or not virile, and also retains the focus on women, then, so it’s a double benefit for that. But if you’re not counted, you don’t count. It’s something that Horace Sheffield said, but I think we can deduct it too if you’re not recognized and acknowledged, it goes along with not being counted.

Christine Erickson: Absolutely. Thank you for that, Robin. I think that goes for all genders, which is how we’re approaching it from the Institute. You’re absolutely right.

Thank you so much to our guests today. We are unfortunately out of time. We could continue this conversation for a long time. I appreciate your brilliant input in everything that you’ve shared here today with our listeners and our readers.

As always, we welcome your questions and comments on any of our platforms to continue the conversation. Please join us again next week.

And to our community and beyond, may you always find the people and places, where you’re celebrated. Goodbye for now.

You can support the work of the New Legacy Institute by becoming an individual or organizational member or with sponsorship or volunteering opportunities. It is the only policy institute in the world that focuses on the global impact of pronatalism and which brings a social justice lens to the inequitable treatment of people without children. The New Legacy Institute is currently entirely self-funded and needs your support!

What's your experience?