RACHEL GILES is a writer, lecturer and editor on art and design and has worked for the National Gallery, Tate, V&A, Gagosian and other galleries and museums. She grows and sells flowers from her cutting garden in London and is passionate about nature’s ability to heal. In 2014 she attended one of Gateway Women’s Reignite Weekends and in 2016 she completed her art history MA dissertation on the visual representation of infertility and childlessness at Birkbeck, London, with distinction. She spoke at Fertility Fest 2018 and co-curated Arts at ESHRE – Fertility Fest’s visual art exhibition – in Barcelona in 2019. She is the author of Bloom: Art, Flowers and Emotion (2021) published by Tate and you can connect with her on Instagram @rachelgileswriter on Twitter @rachgileswriter or by email at rachel.giles@zen.co.uk

RACHEL GILES is a writer, lecturer and editor on art and design and has worked for the National Gallery, Tate, V&A, Gagosian and other galleries and museums. She grows and sells flowers from her cutting garden in London and is passionate about nature’s ability to heal. In 2014 she attended one of Gateway Women’s Reignite Weekends and in 2016 she completed her art history MA dissertation on the visual representation of infertility and childlessness at Birkbeck, London, with distinction. She spoke at Fertility Fest 2018 and co-curated Arts at ESHRE – Fertility Fest’s visual art exhibition – in Barcelona in 2019. She is the author of Bloom: Art, Flowers and Emotion (2021) published by Tate and you can connect with her on Instagram @rachelgileswriter on Twitter @rachgileswriter or by email at rachel.giles@zen.co.uk

The Plant-Woman, by Rachel Giles

In Ovid’s narrative poem Metamorphoses, Daphne, a female nymph, transforms herself into a laurel tree to escape the clutches of her obsessive pursuer, Apollo. Until last year I was unaware of the power of Greek mythology to speak to my own story, but stumbled across this woman-into-a tree episode when I was researching and writing my book Bloom: Art, Flowers and Emotion in 2020, during the first lockdown in the UK.

Written in 8AD, Metamorphoses is full of astonishing and beautiful moments of transformation – such as human into stag, fungus into human – often set within a story of violence or desperate pursuit. It’s no surprise that these stories have inspired all kinds of literature, theatre, painting and music, as art is in the business of using the mutability of the natural, physical world to point to deeper truths.

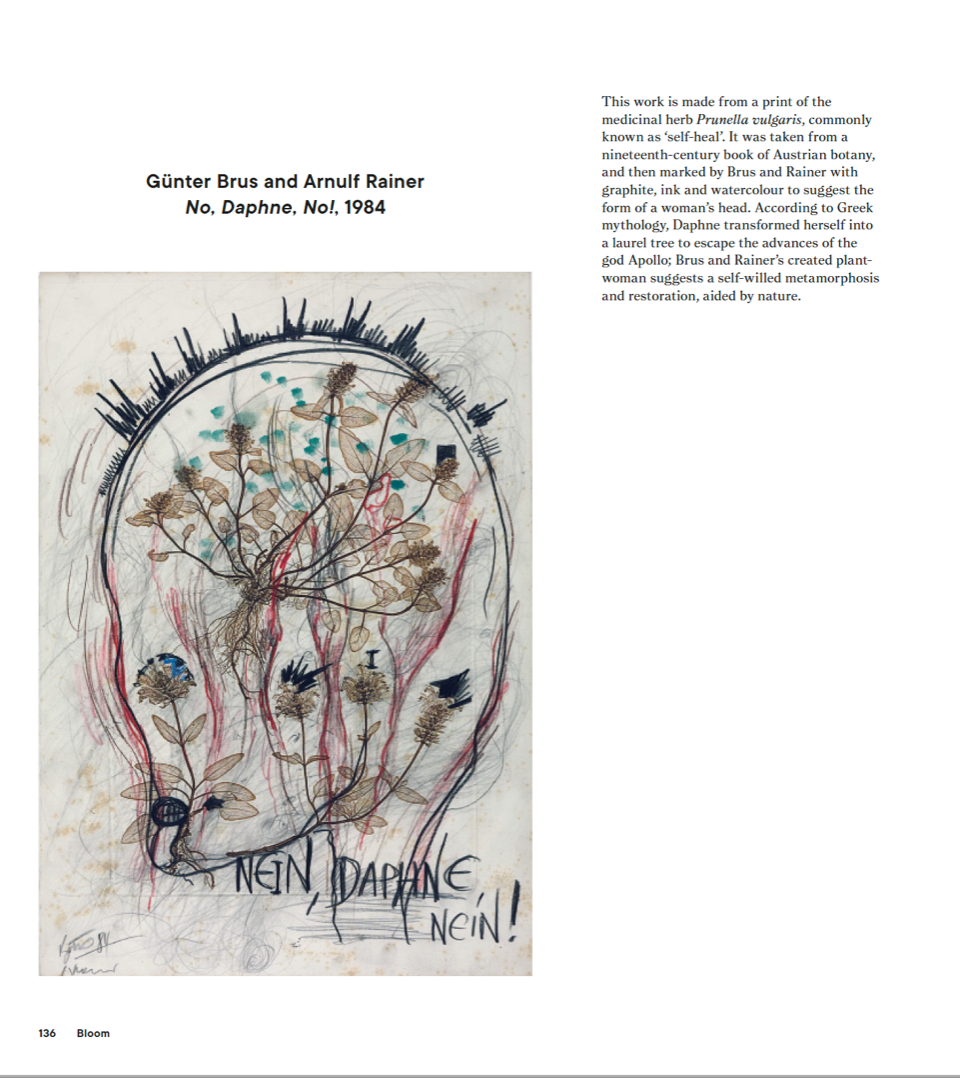

Daphne features in a work in Tate’s collection by the Austrian artists Günter Brus and Arnulf Rainer, No, Daphne, No! (1984). The basis of this picture is what is known as a nature print – a method of botanical image-making dating back to the mid-nineteenth century, before photography came along. In the technique, plants, butterflies, fossils and feathers were pressed into a soft lead plate to make an impression on paper. Brus and Rainer repurposed just such a print from an 1873 book of Austrian marsh and meadow flowers, made from a plant called Prunella vulgaris, commonly known as ‘self heal’ and used in early medicine for its ability to salve a wound.

Daphne features in a work in Tate’s collection by the Austrian artists Günter Brus and Arnulf Rainer, No, Daphne, No! (1984). The basis of this picture is what is known as a nature print – a method of botanical image-making dating back to the mid-nineteenth century, before photography came along. In the technique, plants, butterflies, fossils and feathers were pressed into a soft lead plate to make an impression on paper. Brus and Rainer repurposed just such a print from an 1873 book of Austrian marsh and meadow flowers, made from a plant called Prunella vulgaris, commonly known as ‘self heal’ and used in early medicine for its ability to salve a wound.

Tearing the print from its binding, Rainer made a series of obliterating marks on it in pencil, passing it onto Brus, who drew a felt-tip pen outline of a woman’s head on top, creating a form that is part-human, part-plant. I call her the plant-woman. It’s a beautiful, scratchy silhouette, with the ghostly impressions of self heal at its centre. The work suggests Daphne’s self-willed metamorphosis where, exhausted and hounded by the chase, she has no option but to transform.

No, Daphne, No! resonates with my own journey through the grief of involuntary childlessness. Once motherhood was no longer an option, my own Plan B – which has never felt like an orderly, linear project – began around seven years ago in a Gateway Women Reignite workshop (created by Jody Day). That space gave me the chance, in a group of like-minded women, to stir some blurry memories about what I used to be like before that whole damn Odyssey started in my thirties – the quest to have children.

I walked out of that room with a bunch of post-it notes and some new fellow travellers, but also with the first hopeful glimmers of what it could feel like to be ‘me’ again – not what society expected of me. The excoriating experience of not becoming a mother has left permanent scars – I’m reminded of the forests of cork oak trees I’ve seen in Portugal with sections of bark viciously gouged away to expose vulnerable, red-raw wood. But as I’ve sloughed off those layers, something more organic and perhaps more authentic has emerged.

My grief has not disappeared, and a kernel of it never will, but there has been healing, partly through the community of people I’ve found and partly through reconnecting with my own unique essence, the things that make me tick, such as writing, art, design and music. That was enough to inspire me onwards. I’ve made wrong turns and gone backwards, and there have been further losses and disappointments – but as my hurting core has slowly pushed outwards, like the rings of a tree, I feel more able to brace against the so-called ‘regular’ losses of life.

Above all, I found immense solace in a 3 metre by 5 metre patch of earth which a neighbour gifted me when she kindly let me share her allotment about five years ago, which I use as a cutting patch. Growing flowers has been a lesson for me in seeing nature’s cycles close up. I’ve observed that some seeds grow, and some don’t. Some flowers bloom, while others shrivel. Where I once raged against my body for letting me down, I now see that I am simply part of nature’s randomness and refusal to be fully controlled. Which is brutal, but also comforting.

Above all, I found immense solace in a 3 metre by 5 metre patch of earth which a neighbour gifted me when she kindly let me share her allotment about five years ago, which I use as a cutting patch. Growing flowers has been a lesson for me in seeing nature’s cycles close up. I’ve observed that some seeds grow, and some don’t. Some flowers bloom, while others shrivel. Where I once raged against my body for letting me down, I now see that I am simply part of nature’s randomness and refusal to be fully controlled. Which is brutal, but also comforting.

In its muteness and ‘otherness’, nature has also helped me, when I was numbed and voiceless, to feel a gamut of emotions, from sadness and wonder to absolute joy – the dependable joy that even in the midst of depression can rise up when picking an armful of dahlias and nicotiana – pure, wordless colour and form – and passing that joy to someone else.

I cannot be allowed to forget that flowers are the sex organs of plants, nor that the driving force of nature is survival and self-replication. The artist and iris breeder, Cedric Morris, said the qualities he admired most in the genus was not their beauty but their determination to reproduce: ‘the attributes of grimness, ruthlessness, lust and arrogance’.

Whilst I have not succeeded in replicating myself, I can observe the cycle happening in my cutting garden and also influence it – giving myself an agency I had utterly lost for a good decade. Standing on my plot, looking at all its aliveness and chaos, I feel grounded and regenerated. I also feel bereft, come October, when my frost-bitten dahlias are pale, clammy ghosts of themselves and fade away. It’s all here, in this small patch of land sandwiched between the A3 and suburbia: life, death and rebirth.

When I started writing a book about flowers in Tate’s collection, I wondered what angle to take, and I wondered why artists depict flowers so obsessively. In the middle of a pandemic, it came to me: beyond the challenge of representing colour and form they stand for emotion. Flowers accompany the rituals of life events, transformation from one state to another: non-existence to birth, singleness to betrothal, life to death. So they can stand for joy, abundance and wonder; fertility, lust, love, and mystery; and at times of loss, grief, nostalgia and longing. More than anything, especially in the spring, they stand for hope, new promise and creativity. The pandemic made us painfully aware of our emotions and of nature’s healing power. Flowers are having a moment in mass culture, and seem, from my Instagram feed, more important than ever.

By chance, No, Daphne No! ended up being the very last image of Bloom, a fitting note to end on in a book that has been part of my own self-willed transformation.

Of course, we don’t heal alone – we need community too: but we also need to rediscover our identity and self-determination after involuntary childlessness, and a way to self-heal. If I cannot replicate myself, then taking my place in the natural world, becoming a part of it, at least learning from it, is a highly respectable Plan B.

And inevitably it has led me to into more new communities, conversations with other growers, and the chance to make my local environment more colourful, better for wildlife, and more inspiring for others. A patch of earth or even a window box is a good place to start. A packet of self-heal seeds arrived in the post a few days ago; I can’t wait to sow them.

Bloom: Art, Flowers and Emotion (2021) by Rachel Giles is published by Tate and available here.

RACHEL GILES is a writer, lecturer and editor on art and design and has worked for the National Gallery, Tate, V&A, Gagosian and other galleries and museums. She grows and sells flowers from her cutting garden in London and is passionate about nature’s ability to heal. In 2014 she attended one of Gateway Women’s Reignite Weekends and in 2016 she completed her art history MA dissertation on the visual representation of infertility and childlessness at Birkbeck, London, with distinction. She spoke at Fertility Fest 2018 and co-curated Arts at ESHRE – Fertility Fest’s visual art exhibition – in Barcelona in 2019. She is the author of Bloom: Art, Flowers and Emotion (2021) published by Tate and you can connect with her Instagram: @rachelgileswriter on Twitter @rachgileswriter or on email at rachel.giles@zen.co.uk

What's your experience?